Arbeidspakke: Mandatory Reporting of Intimate Partner Violence (MANREPORT-IPV)

Publisert: 05.03.2021

1. Excellence

1.1 State of the art, knowledge needs and project objectives

“That damned confidentiality. Well, take, for example, when the police came to the (name of the village). I do not know if there was any communication between the agencies on such things. And they must, God in heaven, communicate, people need to talk. The confidentiality is more to protect social agents. In this case, it was completely wrong.” (Vatnar, Friestad, & Bjørkly, 2017, p.399).

The quotation is from a Norwegian study on intimate partner homicide (IPH). Interviews with the bereaved showed that they had observed what they in hindsight perceived as risk factors for intimate partner homicide and that these disclosures had raised concern and several attempts to help (Vatnar et al., 2017). Among efforts to protect individuals perceived to be at risk of harm, countries in some parts of the world have adopted legislation requiring professionals to report cases of IPV, or suspected IPV injuries, to the police or the criminal justice system. The most commonly used term for this is mandatory reporting (Jordan & Pritchard, 2018; WHO, 2013). The purpose of mandatory reporting is to protect IPV victims from risk of harm, to relieve victims of having to report abusive partners themselves, and to improve the involvement of law enforcement and criminal justice response (Jordan & Pritchard 2018; Rodriguez, Sheldon, & Rao, 2002). Furthermore, mandatory reporting sends a signal to abusive partners that IPV is a serious crime (WHO, 2013) and establishes third-party documentation that may be critical to a criminal or civil legal action (Antle, Barbee, Yankeelov, & Bledsoe, 2010). Even though its intention is to protect, mandatory reporting of IPV is a controversial issue. Critics argue that reporting requirements undermine victims’ autonomy and decision making and may decrease willingness to disclose abuse and seek treatment for IPV injuries (e.g. Lippy, Jumarali, Nnawulezi, Williams, & Burke, 2020; Rodriguez et al., 2002). Supporters of the laws argue that mandatory reporting may increase victims’ safety by requiring professionals to report potential threats and thereby redu

ce the danger to victims (e.g. Antle et al., 2010).

A systematic review concerning mandatory reporting of IPV (Vatnar, Leer-Salvesen, & Bjørkly, 2019) indicated the following:

(1) IPV victims were generally supportive of the law that professionals should be required to report IPV. However, subsamples opposing mandatory reporting were presented as main findings in a substantial number of studies.

(2) Group differences between abused or non-abused women were mixed. Some studies found significant group differences (e.g. current abuse, ethnicity, marital status, having children) regarding attitudes to help-seeking if the professionals were obligated to report, whereas others did not. Some of the studies group differences, however, conducted analyses that also included dependent variables – for example, as an independent variable, positive attitudes toward mandatory reporting increased willingness to see a doctor despite health professionals’ obligation to report.

(3) Knowledge about mandatory reporting of IPV among professionals was insufficient. There were indications of group differences among professional disciplines and gender regarding compliance. Primary care providers were less likely than emergency physicians to comply when patients objected. More women than men supported mandatory reporting laws.

(4) Very few professionals had actually reported IPV under mandatory reporting.

(5) None of the included studies investigated perpetrators’ attitudes to mandatory reporting of IPV.

Empirical research appears to be scarce, with moderate to high degree of bias and with only limited recent development: six studies within the last 10 years (Vatnar et al., 2019). However, the World Health Organization has concluded that mandatory reporting of IPV by healthcare providers is not recommended (WHO, 2013). The findings of our review did not provide empirical evidence supporting this advice (Vatnar et al., 2019). On the contrary, the results from the highest quality studies contradicted the WHO recommendation (Vatnar et al., 2019). Above all, we found indications of attitudes opposing mandatory reporting among the researchers in several studies - that is, they systematically reported findings of statistical minorities who opposed mandatory reporting as being more significant than those of statistical majorities who supported mandatory reporting of IPV (Vatnar et al., 2019). Furthermore, they indicated that mandatory reporting laws were the major or only barrier to IPV help-seeking (Vatnar et al., 2019). The gap between professionals having (1) strong attitudes opposing or supporting mandatory reporting, (2) in a mixture with professionals actually having limited awareness and (3) scarce experience of mandatory reporting of IPV demands further investigation, which is the purpose of the present application.

IPV comprises physical and sexual violence, stalking and psychological aggression (including coercive tactics) by a current or former intimate partner (Breiding, Basile, Smith, Black, & Mahendra, 2015). Worldwide, almost one third of women who have been in a relationship have experienced physical and/or sexual violence by an intimate partner (WHO, 2013). A systematic review of the global prevalence of intimate partner homicide, with data obtained from 169 countries, found that 13.5% of all homicides were committed by an intimate partner. The proportion was six times higher for female victims than for male victims (Stöckl, Devries, Rotstein, et al., 2013). Interpretations of these findings conclude that at least one in seven homicides globally and more than a third of femicides are perpetrated by an intimate partner.

Norway has statutory mandatory reporting for every citizen. Yet we found no studies limited to the topic of mandatory reporting of IPV in Norway (Vatnar et al., 2019). The lifetime prevalence of severe IPV in Norway is 8-10% for women and 2% for men (Thoresen & Hjelmdal, 2014). Moreover, there is an average incidence of eight intimate partner homicides every year, constituting ¼ of homicides in Norway every year (Kripos, 2019). Research has demonstrated that 7 out of 10 IPH victims and 8 out of 10 perpetrators (in Norway) had been in contact with professionals prior to the homicides (Vatnar et al., 2017). However, in these contacts with IPH victims, risk was assessed in only 4 out of 10 cases and, for perpetrators, 3 out of 10. Furthermore, assessed risk was forwarded to other professionals in only 14% of the cases (Vatnar, 2015). In the majority of IPH (71%), one or more previous episodes of IPV had been identified. In 5 out of 10 IPHs, more than five previous episodes of IPV had been identified (Vatnar et al., 2017). These results correspond to international studies. , where previous IPV is seen in 65-80% of IPH and previous repeated IPV, in 25-65% (e.g. Campbell, Glass, Sharps, Laughon, & Bloom, 2007). This evidence suggests that in a majority of IPH cases, there is a potential for intervention and prevention. In relation to this, individuals who had contacted any of the professional services were left with the impression that none of these agencies had appreciated the gravity of the situation (Vatnar et al., 2017).

The overall objective of MANREPORT-IPV is to expand empirical knowledge about mandatory reporting of IPV to inform more effective prevention of serious cases of IPV and IPH. The project will contribute to innovation by providing new knowledge about what may hinder and what may facilitate mandatory reporting, thus building a foundation for more evidence-based recommendations and interaction in law enforcement and the health and social services.

Operational aims:

(1) to investigate the practice of mandatory reporting of IPV in Norway.

(2) to scrutinize professionals’ experiences, attitudes, and awareness pertaining to mandatory reporting.

(3) to compare the different professional groups in the study and analyse horizontal interaction in preventing IPV.

(4) to investigate IPV help-seekers’ (victims and perpetrators) experiences, attitudes and awareness pertaining to mandatory reporting of IPV.

1.2 Research questions and hypotheses, theoretical approach and methodology

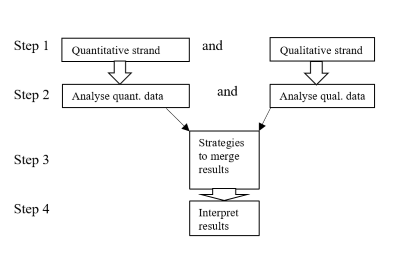

Aim of the study: What experiences, awareness, and attitudes do professionals and IPV help-seekers in Norway have concerning mandatory reporting of intimate partner violence? The aim is operationalized in four research questions wrapped in three working packages in a mixed methods study with a convergent parallel design (cf. below 1.3).

1. What is the prevalence of mandatory reporting of IPV in Norway? (WP1)

2. What are professionals’ awareness of, attitudes to, and experiences with mandatory reporting of IPV?

a. Are there group differences? (WP2-3)

3. What are professionals’ thresholds for mandatory reporting of IPV and cooperating with other entities in the service system? (WP2)

4. How do IPV help-seekers (victims and perpetrators) perceive (awareness, attitudes and experience) mandatory reporting of IPV?

a. Are there group differences? (WP2-3)

User involvement is a key to all the stages of the project, from the planning to the conduct of the study and the dissemination of the results. MANREPORT-IPV consists of five working packages (WP). Three are dedicated to research and two involve dissemination and project management (cf. Section 3.2). The WPs are closely connected, and they inform each other to provide rich data. The purpose of the convergent design is to obtain different but complementary data on the same topic (Morse,1991).

Working package (1) Systematic text studies and juridical analysis.

The project will start with a descriptive explorative study. Two recent legal studies discussed what kind of knowledge could establish a duty to report IPV for professionals, but did not aim to explore how much the professionals knew about the legal questions arising (Holmboe, Leer-Salvesen, & Vatnar, 2019a, 2019b). Moreover, previous research by the project group on the sociodemographic and the interactional aspect of IPV on help-seeking behavior indicates that more than 40 % of the women had been in contact with at least two agencies (e.g. police, shelter, family doctor, psychologist; cf. Vatnar (2009)). Thus, the first step is to provide an overview of the phenomenon under investigation by legal theory and methods. The next step is to create a foundation for conducting a multidisciplinary and explorative empirical study on mandatory reporting in Norway. The material for the systematic text studies consists of court documents from IPV cases (The Penal Code §§ 282 and 283) and mandatory reporting cases examined by the Norwegian Board of Health Supervision or the Norwegian Board of Health Personnel within the last 30 years.

The aims of WP1 are

(1) to estimate the prevalence of documentation of mandatory reporting of IPV in Norway in court documents and other relevant juridical sources.

(2) to analyse professionals’ experiences with, awareness of, and attitudes about mandatory reporting of IPV in court documents and other relevant juridical sources.

(3) to discuss and establish the juridical frame and threshold for mandatory reporting of IPV, both of which are necessary for the analysis in WP2-3.

Working package (2) Qualitative analyses of experiences, awareness and attitudes toward mandatory reporting of IPV.

To provide details and in-depth data of professionals’ and help-seekers’ experiences, awareness and attitudes, we will conduct qualitative individual interviews, analysed by systematic text condensation. Personnel at emergency medical departments and domestic violence shelters were among the professional groups that had some degree of experience with mandatory reporting (Vatnar et al., 2019). Accordingly, the sample of professionals will be drawn from these contexts, including (1) professionals responsible for treating or helping IPV victims and perpetrators (nurses, doctors, clinical psychologists, shelter professionals), (2) professionals who respond to reports about IPV (police, child protective services) and (3) help-seekers in IPV cases.

By using semi-structured qualitative interview guides, WP2 will examine what factors affect professionals’ decision making regarding mandatory reporting. We will investigate how these professionals reason about their choices of actions, their professional roles, their responsibilities, and about cooperating with other entities in the service system when handling possible IPV cases. The analysis will center on what may hinder and what may promote mandatory reporting. Moreover, we will explore IPV help-seekers’ experiences, attitudes and awareness of mandatory reporting. How does mandatory reporting affect help-seekers’ confidence in the service system and the experiences of the treatment they receive? Individual qualitative interviews are better suited for our purposes than focus groups due to the sensitive nature of our research topic. We highlight the risk of self-protection bias and group-think effects that may occur in focus groups. Two focus group studies of IPV victims, with results clearly deviating from other studies, illustrate these dangers (Antle et al., 2010; Rodriguez, Craig, Mooney, & Bauer, 1998).

In previous research projects, we have established contact with heads of the following support services that aid victims/survivors and perpetrators: shelters, Alternative to Violence, Anger management Brøset, the police, and family counseling offices (Vatnar & Bjørkly, 2008; Ørke et al., under review). These agencies have agreed to contribute to recruit participants for this project from among the help-seekers and staff. Routines for recruitment have been established. We will also increase recruitment of health professionals and apply the same procedure for recruitment as in previous projects. For this purpose, we have established contact with the Institute for Studies of the Medical Profession (Legeforskingsinstituttet). The support services will get information about this particular project and documents for participants’ informed consent. Once participants have accepted, they will be contacted by the project leader or a PhD student.

The aims of WP2 are

(1) to examine experiences, awareness, and attitudes toward mandatory reporting in professional groups with different roles and responsibilities pertaining to IPV

a. to compare professional groups.

b. to analyze experiences from and attitudes towards interaction within and across professional

disciplines in preventing IPV.

(2) to explore IPV help-seekers’ experiences, attitudes and awareness of mandatory reporting of IPV by thematic cross-case analyses within a phenomenological tradition.

Working package (3) Quantitative investigation of professionals’ and help-seekers’ perceptions and experiences with mandatory reporting of IPV.

The aims of WP3 are

(1) to identify predictors of supporting or opposing mandatory reporting of IPV among professionals and IPV help-seekers.

(2) to pre-and post-test professionals’ awareness and change of attitudes and experience by interventions - part of a master programme in mental health and social services.

(3) to compare awareness, attitudes and experience with mandatory reporting of IPV among groups of professionals and IPV help-seekers.

(4) to ascertain if the law of mandatory reporting of IPV deters help-seekers from getting care.

The Institute for Studies of the Medical Profession has provided their validated questionnaires (repeated measurements, 2,200 doctors, every other year since 1992) for measuring attitudes, awareness and experiences, covering societal and organisational conditions for professional work, ethics, professional values and prioritisation. These questionnaires will be adjusted for measuring mandatory reporting of IPV. The questionnaires will, in cooperation with the heads of the agencies, be distributed to representative samples of (A) professionals and (B) IPV help-seekers chosen from the same professions and services as in WP2 (cf. Chapter 1.2). The association between awareness, attitudes, experience factors and the following independent variables will be determined: (1) different groups of professionals and IPV help-seekers, (2) professionals and help-seekers supporting or opposing mandatory reporting of IPV and (3) professionals and help-seekers having experienced mandatory reporting or not. Advanced multivariate regression analysis will be conducted to measure the purposes of WP3. The stepwise options recommended for regression analysis in small samples will be used (Altman, 1991; Pallant, 2010). Statistical analyses will be performed using the statistical program package SPSS and Stata. In order to attain statistical power to compare subgroups, we aim at 40 participants in each subgroup of both (A) professionals N = 240 and (B) help-seekers N = 160. From previous projects, we have experienced this to be achievable within the context of a PhD study.

Theoretical approach.

We understand professionals’ decisions regarding mandatory reporting of IPV as complex processes characterised by perceptual uncertainty and high stakes. The consequences of making a wrong decision, or of postponing a decision, might be detrimental. We will apply conceptual clarifications that enable us to study two distinct, although related, aspects of professional discretion. First, the use of discretion has a structural dimension, which means that it is restricted by normative frames (Molander, 2018). This underscores the significance of analysing the normative frames and juridical thresholds that influence and restrict professionals’ room to maneuver. Such analysis constitutes the major part of WP1. Second, we highlight discretion as an epistemic category, as a form of practical reasoning that involves finding justifiable answers to questions (Molander, 2018). Analytically applied, this concept enables us to investigate which norms, laws, knowledge, experience and attitudes the informants use to explain and justify their choices when encountering IPV, (cf. WP2). Moreover, The Decision Making Ecology (e.g. Fluke, Baumann, Dalgleish, & Kern, 2014) provides a theoretical basis for understanding the context, process and outcomes of decision making regarding mandatory reporting of IPV. It enables us to analyse different factors determining professionals’ willingness to take action (Fluke et al., 2014), including characteristics of the individual case (e.g. type and severity of maltreatment), of the professional (e.g. experience, knowledge) and organisational (e.g. policy, workload), and external characteristics (e.g. critical events, funding). We will adapt the model to the analysis of mandatory reporting of IPV.

Attitudes have typically been studied as one component of a three-part system: the cognitive, the affective and the behavioural component. Consistency between beliefs and attitudes is a common occurrence. A major reason for studying attitudes is the expectation that they enable prediction of behaviour. Classical studies have illustrated that behaviour is determined by many factors other than attitudes and that these affect attitude-behaviour consistency. In general, attitudes tend to predict behaviour best when they are strong and consistent, based upon the person’s direct experience and specifically related to the behaviour being predicted (Atkinson, Atkinson, Smith & Hilgard, 1987). The most influential theory of this sequence has been Festinger’s theory of cognitive dissonance (Festinger, 1957) and induced compliance (Festinger & Carlsmith, 1959). This theory predicts that engaging in behaviour that is counter to one’s attitudes creates pressure to change the attitudes so that they are consistent with the behaviour.

Our systematic review pinpoints the need to investigate the relationship between the professional’s experiences, attitudes (accessibility and centrality) and awareness (Vatnar et al., 2019), especially because failures to comply may be an issue explaining limited professional experience with reporting (cf. Cho et al., 2015, Aved et al., 2007). Reasoned action approach (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010) affords resources to examine the association between beliefs and behaviour. Following this theory, the professional’s beliefs about intimate partner violence and mandatory reporting “serve to guide the decision to perform or not perform the behavior in question” (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010). Therefore, we will distinguish and analyse three different beliefs. First, the professional’s beliefs about the positive or negative consequences associated with mandatory reporting of IPV. Such outcome expectancies are assumed to determine people’s attitudes toward personally performing the behaviour (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010). The beliefs about the consequences of unsubstantiated reports and about failing to report when mandated will be our primary interest. Second, the professional’s beliefs about whether significant individuals or groups would approve or disapprove their decision regarding mandatory reporting. This involves an analysis of perceived norms, of the perceived social pressure to engage, or not engage, in the behaviour. Third, Reasoned action approach enables an investigation of the professional’s beliefs about personal (e.g. skills, training) and organisational factors that can help or impede their attempts to carry out the behaviour.

1.3 Novelty and ambition

The project has been designed to investigate mandatory reporting from the perspectives of both (1) IPV victims and perpetrators and (2) professionals, including doctors, nurses, clinical psychologists, domestic violence shelter workers, child protective services and the police. The ambition is to improve the empirical knowledge of mandatory reporting of IPV. The project will generate new knowledge to help professionals mitigate IPV. Studying professionals, victims and perpetrators enables us to analyse horizontal interactions between service providers with different responsibilities concerning IPV. The multidisciplinary investigations outlined in Section 1.3 enable us to study the mandatory reporting of IPV from juridical, ethical and psychological perspectives, thus adding rigor and complexity to the analysis. In addition, we will extend prior research by addressing both experiences, awareness and attitudes pertaining to mandatory reporting of IPV. Moreover, MANREPORT-IPV investigates facilitators or barriers to mandatory reporting of IPV, not just theoretically, but also in the relevant contexts. No other studies have investigated perpetrators’ awareness, attitudes or experiences with mandatory reporting of IPV, and no other studies have combined professionals’ and IPV help-seekers’ perspectives within the same design (Vatnar et al., 2019).

2. Impact

2.1 Potential for academic impact of the research project

Our systematic review concluded that the most striking finding in the research field is the scarcity of scientific studies (Vatnar et al, 2019). In addition, there is a lack of knowledge about the extent of mandatory reporting in professional practices in Norway. Moreover, we have documented researchers displaying strong attitudes about mandatory reporting of IPV (Vatnar et al., 2019), even to the extent of suggesting decriminalisation of IPV as a better way to protect victims from harm (Lippy et al., 2020).

Our multidisciplinary project is innovative in scope and ambition. The design enables a multifaceted exploration of mandatory reporting. MANREPORT-IPV will contribute to the methodological advancement of the research field by being the first research group to adjust validated instruments developed to measure societal and organisational conditions for professional work, ethics and professional values into measures of awareness, attitudes and experience in mandatory reporting of IPV (Vatnar et al., 2019). Thus, MANREPORT-IPV offers the prospect of improving the foundation for valid findings in future studies and informing professional work.

The primary output of the project will be at least 22 scientific articles, the development of competence (foremost 5 PhDs, 2 post docs) and a leading milieu for research on mandatory reporting of IPV. With only nine small-scale studies of professionals’ attitudes and awareness of IPV internationally, the extensive and multidisciplinary MANREPORT-IPV project will contribute significantly to advancing the knowledge base in this field of research.

2.2 Potential for societal impact of the research project

MANREPORT-IPV addresses a research topic of major importance for IPV victims, perpetrators and professionals, as well as for policy makers. Intimate partner violence is a key societal challenge and public health problem (Ministry of Justice and Public Security, 2014) both in Norway and globally. The Sustainable Development knowledge platform highlights the magnitude of IPV worldwide: “1 in 5 women and girls between the ages of 15-49 have reported experiencing physical or sexual violence by an intimate partner within a 12-month period” (United Nations, 2019). Our proposal has relevance for the sustainable development goal of “Good health and well-being” (United Nations, 2019). However, we directly address Goal 5 “Gender equality” which focuses on IPV. Women are far more likely to be killed by an intimate partner than by anyone else (e.g. Campbell et al., 2007; Vatnar et al. 2017). The output of the project has potential to address Targets 5.2 “Eliminate all forms of violence against all women and girls in the public and private spheres” and 5.C “Adopt and strengthen sound policies and enforceable legislation for the promotion of gender equality and the empowerment of all women and girls at all levels”.

The output has relevance for institutions at a national level and for policymakers. Even though mandatory reporting of IPV was intended as a means of enhancing victims’ safety, preventing future violence and improving the criminal justice response, the body of knowledge is inconclusive and offers no valid evidence to support a major attitude, behaviour or policy directive toward the subject (Vatnar et al., 2019). The outputs of the project may, thus, contribute to improving the professional care offered to IPV help-seekers. Moreover, MANREPORT-IPV will expand the empirical knowledge on mandatory reporting of IPV to inform a more effective and evidence-based prevention of serious cases of IPV and IPH. An implementation of the research results may lead to increased interdisciplinary interaction in IPV-cases, higher rates of preventing serious IPV, and to innovation in terms of higher service quality provided to IPV help-seekers.

In October 2018, the Norwegian government appointed a committee to review intimate partner homicide cases. The purpose of the review is to identify possible challenges, insufficiencies and system failures in the public support services’ handling of such cases prior to the homicides. Possible examples of system failure may be lack of or inadequate interaction or communication between services, inadequate regulations, poor understanding of existing regulations and the lack of knowledge, organisational culture, the absence of essential services or coordination mechanisms or other factors.

3. Implementation

3.1 Project manager and project group

The project manager, Kjartan Leer-Salvesen, has prior experience as a project leader from Research & Development and from projects in humanities involving extensive international cooperation (cf. CV). Leer-Salvesen’s primary research interests are mandatory reporting and professional discretion. Solveig K. B. Vatnar is the co-manager of the project and a professor of clinical psychology at MUC and researcher at OUS (cf. CV). Her expertise is in the fields of intimate partner violence and homicides.

Morten Holmboe is a lawyer with expertise on mandatory reporting and a professor at NPUC. Holmboe has published several books and articles on criminal law, criminal procedure, human rights and restorative justice. Stål Bjørkly is a professor of clinical psychology and senior researcher at MUC and OUS with a high level of expertise in research on perpetrators and victims of violence. Kevin Douglas is a professor of clinical forensic psychology at Simon Fraser University, Canada, and a Senior Research Advisor at OUS. Douglas has excellent expertise of relevance to the project, including violence risk assessment, interventions for reduction of violence. Idun Moe Hammersmark is the head of the national secretariat for the Domestic Violence Shelters (DVS). DVS has played an important role in all stages of the work leading to this proposal. Finally, Professor Emeritus Petter Laake has expertise that complements that of the principal investigators. Laake’s main contribution will be his advanced expertise in statistical analysis, which will be of paramount importance.

WP1. Systematic text studies and juridical analysis (cf. Section 1.3).

Researchers: Morten Holmboe (responsible), PhD student, Solveig Vatnar, Kjartan Leer-Salvesen and 1 project worker.

WP2. Qualitative investigation of experiences, awareness and attitudes to mandatory reporting of IPV (cf. Section 1.3).

Researchers: Solveig Vatnar (responsible), two professor scholarships, PhD student, Kjartan Leer-Salvesen, Morten Holmboe and 2 project workers.

WP3. Quantitative investigation of professionals’ and help-seekers’ perceptions and experiences with mandatory reporting of IPV (cf. Section 1.3).

Researchers: Solveig Vatnar (responsible), Stål Bjørkly, Petter Laake, 3 PhD students, Kevin Douglas, Kjartan Leer-Salvesen, 1 project worker.